August is Women in Translation month, and as editors and translators here at Norvik Press we would like to make a bit of a fuss about ours. The Press has always prioritised Nordic women writers, whether it be lesser-known classics like Camilla Collett (The District Governor’s Daughters) and Fredrika Bremer (The Colonel’s Family) or modern writers so far little known in English, such as the Danish Dorrit Willumsen, the Norwegian Helene Uri and the Icelandic Svava Jacobsdóttir. All of our directors and the majority of our translators are also women. This month we are highlighting three of our major women writers: Amalie Skram (Norway), Kerstin Ekman (Sweden) and Kirsten Thorup (Denmark).

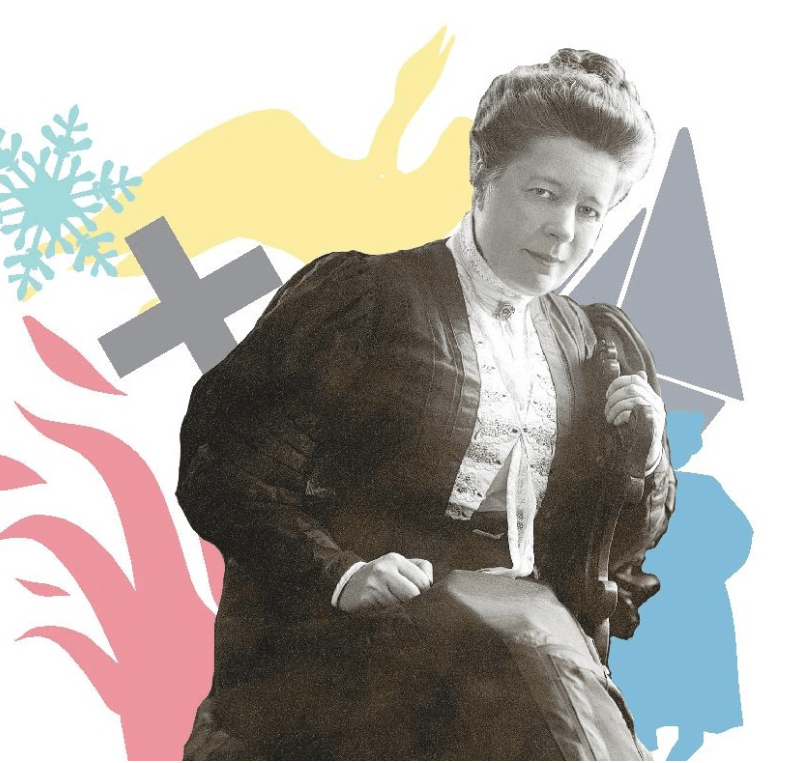

Amalie Skram

by Janet Garton

Born in 1846 into a relatively prosperous family in the bustling port of Bergen, Amalie Skram had an unusual early life for a middle-class woman in the mid-nineteenth century; at the age of eighteen she married a ship’s captain and sailed the world with him and their two sons. Her adventurous life came to an abrupt stop when in 1877 she filed for an acrimonious divorce. Soon after she embarked on a literary career which brought her into contact with Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Georg Brandes and eventually Erik Skram, with whom she fell in love and who became her second husband in 1884. From then on she earned a precarious living as a writer, living in Copenhagen and writing novels, many of which have become enduring classics. She died in 1905 at the age of 58.

Norvik Press has published three of Amalie Skram’s novels, Lucie (1888), Fru Inés (1891) and Betrayed (1892), all translated by the indefatigable US translators and Skram enthusiasts Katherine Hanson and Judith Messick. The novels are similar in that they all have as central characters women who have been damaged by the contemporary double standard of morality, which encouraged men to be promiscuous whilst punishing women who wanted any sexual freedom – but at the same time they illuminate very different perspectives. Lucie is a girl who has transgressed the norms and is the kept mistress of a civil servant in Kristiania; he falls in love with her and decides to make her a respectable married woman – only to be defeated by her irrepressible high spirits. Fru Inés is a woman trapped in a loveless marriage and longing for sexual fulfilment, but finds when she tries to break free that a dreadful fate awaits her. And Ory in Betrayed is an innocent young girl who marries a ship’s captain, but can not accept or forgive that he has known other women; her probing drives him to despair. The settings of all three novels reflect the author’s wide knowledge of the world. Lucie is set in the Kristiania she knew so well, and brings to life the streets and buildings of that time; Betrayed gives a vivid picture of life on board a sailing ship, and includes a visit to a London full of dance halls and oyster restaurants. Fru Inés takes place in Constantinople, and the sights, sounds and smells reveal Skram’s intimate first-hand knowledge of the city.

As a long-time admirer of Amalie Skram’s writing – I have written a biography of her and published several volumes of her correspondence – I am delighted to say that I am about to start work on a new translation. This is of a very different work than the ones above; it will be the first two volumes of a four-volume series called The People of Hellemyr (1887–98), which is set amongst fisherfolk in and around her native Bergen. It follows the lives of a desperately poor farmer and his family as they struggle to lift themselves out of poverty – a study of lives lived against the odds and the fatal flaws that are passed on from generation to generation.

Kerstin Ekman

by Sarah Death

Kerstin Ekman, doyenne of the Swedish literary scene, has been entertaining and enchanting her readers with a wide sweep of works for over sixty years. This month she reaches the grand age of 90, and she is still busy writing.

Norvik Press is delighted to be the publisher of five of her books. Her extended autobiographical poem Childhood, translated by Rochelle Wright, is a distillation of so much that we learn of Ekman’s life and times from her wider oeuvre. ‘You have to admire the persistence of time/ that it doesn’t grow tired and get stuck’, she writes, and indeed the theme of time thundering onwards is central to her ground-breaking quartet of novels set in a small southern Swedish town, sometimes collectively called ‘Women and the City’ but also known as the Katrineholm quartet, and originally published in Sweden between 1974 and 1983. These were translated into English for Norvik Press by Linda Schenck (three volumes) and me (one volume), both of us long-standing devotees of the author’s work. The series is essentially a women’s eye view of the changes wrought in ordinary people’s lives by events and innovations of the past century and a half, not least the impact of the coming of the railway to a small rural community, where progress and tradition clash. Ekman’s multi-generational cast of characters (who can forget Sara Sabina or Tora, Jenny, Ingrid or Anne-Marie?), artfully woven plots and fine evocations of time and place make this series thoroughly deserving of its ‘modern classic’ label.

Our profound response to special reading experiences lies at the heart of Kerstin Ekman’s latest work, which is being published to coincide with her landmark birthday in August: Min bokvärld (My World of Books, Albert Bonniers förlag, 2023) is an exploration in twenty-four chapters of the reading experiences close to Ekman’s heart, from childhood to the present day. At the time of writing only the table of contents was available, but it is a great indication of the treasure trove in store. One of her choices felt particularly appropriate to me as her reader and translator: The Golden Bough, the classic study of mythology, magic and comparative religion by Scottish anthropologist and folklorist James Frazer. I have more than once found myself consulting it in a quest for details of myths, legends and archetypes that I came across in Ekman’s writing.

From Homer’s Odyssey via a good many nineteenth-century European classics to twentieth-century works by the likes of Philip Roth, Doris Lessing and Ray Bradbury, this is a revealing and substantial bookshelf selection. Emily Brontë sits alongside Albert Camus; Sweden’s Moa Martinson and Norway’s Cora Sandel rub shoulders with Thomas Mann and Russian greats. It is gratifying to see other Norvik authors finding a place here: Herman Bang, Hjalmar Bergman and – naturally – Selma Lagerlöf. Ekman nominates Lagerlöf’s complex Bannlyst, a cry of pain from the aftermath of the First World War that grapples with moral dilemmas still relevant today. Part of Norvik’s prizewinning ‘Lagerlöf in English’ series, this novel was translated for us by Linda Schenck as Banished.

In a pleasing footnote of literary continuity, it is intriguing to see that Kerstin Ekman shares some of her choices with the youthful Lagerlöf, whose discovery of the wonderful world of reading is described in the author’s semi-autobiographical Memoirs of a Child (1930). Ibsen, Dickens, Tolstoy and Turgenev feature on both their lists of favoured authors.

Kirsten Thorup

by Janet Garton

Kirsten Thorup (b. 1942) is the author of a large number of novels – and some plays and poetry – over the last fifty years which have earned her a central place in Danish literature. Her themes and settings are extremely varied and often experimental in terms of narrative perspective and plot. An early success came with Lille Jonna (Little Jonna, 1977), the first in a series of novels about a girl growing up in a rural family on the island of Funen; academically gifted, she battles to gain a good education – which leads to estrangement from her family and roots. The novels reflect the author’s own background and her experience of a similar alienation. Thorup’s most recent work is Indtil vanvid, indtil døden (Unto Madness, Unto Death, 2020), the first novel of a planned trilogy which narrates the trials of Harriet, the widow of a Danish soldier who has died fighting for the Germans on the Eastern Front in 1942. In order to understand his death she travels to Munich that same year, and tries to reconcile the brutalities of the Nazi regime which she witnesses at first hand with her loyalty to her husband’s memory and beliefs.

A few years ago I translated one of Thorup’s novels from 2011, Tilfældets Gud (The God of Chance, 2014). The novel is about two very different women: Ana, a successful Danish financier who is on holiday in Gambia to recover from over-work, and Mariama, a young beach-seller who accosts her on the beach outside her hotel. Ana feels an immediate bond with the girl; she has found ‘her platonic other half which she had been separated from at the dawn of time’, and decides to help her to go to school, eventually moving to London in order to bring her over to educate and foster her. But the situation becomes extremely complicated because of Mariama’s family’s demands and Ana’s own unacknowledged neediness, and the philanthropic urge ends in catastrophe for both.

In this novel Thorup takes up the fraught question of global inequality and our attempts to redress it; what are we doing when we provide so-called aid, and is our help really altruistic or just a sop to our bad consciences? Can our model of what constitutes a good life be applied to other cultures, or are we destroying a functioning social structure and leaving people rootless? The urge to help in the face of extreme deprivation seems laudable, yet it can so easily turn into another form of imperialism.

To order the Norvik Press books highlighted in this blog, please follow the green hyperlinks or request the titles you would like at your favourite bookshop.