Logo for International Women’s Day (IWD) 2023.

The month of March marks both International Women’s Day, on 8 March, and Women’s History Month. In honour of these occasions, this blog profiles our pioneering women writers. We are very proud to have played a part in facilitating access to their work for English-speaking readers – frequently through women translators, and with cover designs by women – and can think of nothing better than inviting them all to a literary dinner party!

Fredrika Bremer (1801–1865) would be the ideal dinner party guest, as she would be very well-placed to supervise all the cooking! We recently re-issued The Colonel’s Family, originally published in two parts (or should that be ‘courses?!’) in 1830–31 and translated by Sarah Death. The novel, which is narrated by a no-nonsense cook-housekeeper with a warm heart and an eye for human weaknesses, now comes to you with an utterly delicious new cover. Pudding, anyone?

Camilla Collett (1813–1895) is a pioneer in Norwegian literature. Translated by Kirsten Seaver, her novel The District Governor’s Daughters portrays a bourgeois society in which marriage is a woman’s only salvation, and follows sympathetically the struggles of one intelligent young woman to break out of this mould.

Amalie Skram (1846–1905) is not for the faint-hearted. Her oeuvre includes Betrayed, Fru Inés, and Lucie, as well as her correspondence: Skram had access to the leading figures of the time, from radical writers and critics to politicians, so there’s plenty to whet one’s appetite!

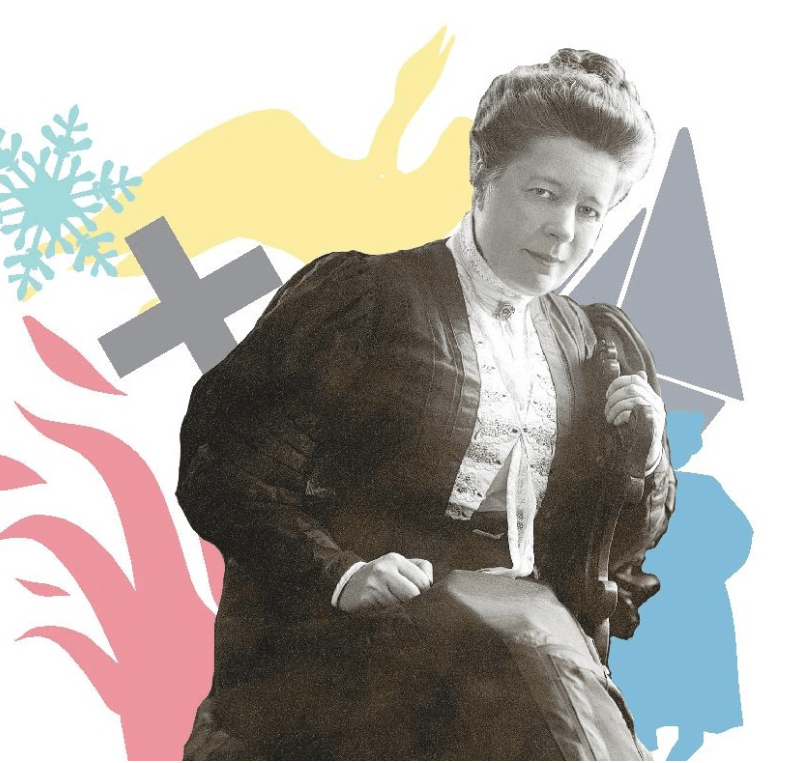

Victoria Benedictsson (1850–1888) would be an esteemed guest at the party. Her first novel, Money, was published in 1885. Set in rural southern Sweden where the author lived, it follows the fortunes of Selma Berg, a girl whose fate has much in common with that of Flaubert’s Madame Bovary and Ibsen’s Nora. The seating plan would need to allow for everyone wanting to converse with Benedictsson about the radical literary movement of the 1880s known as Scandinavia’s Modern Breakthrough.

Selma Lagerlöf (1858–1940): definitely a seat at the head of the table for her! Reading Lagerlöf is life-changing. A good place to start is with our Lagerlöf in English series. You can thank us later!

Elin Wägner (1892–1949): feminist, suffragist, pacifist and environmentalist, Wägner was the author of a prodigious amount of journalism, political pamphlets and prose fiction as well as an acclaimed biography of Selma Lagerlöf (see above!). The edited volume Re-Writing the Script: Gender and Community in Elin Wägner shows how Wägner’s texts outlined bold alternatives to the Swedish welfare state, and how her combined focus on gender and environmentalism anticipated much more recent ecocritical works. The title of her novel Penwoman, about the Swedish women’s suffrage movement, speaks for itself and applies to all the other guests at this soirée.

Hagar Olsson (1893–1978) and Karin Boye (1900–1941) would absolutely be seated together, and we would recommend reading them together, too: Chitambo and Crisis are the perfect modernist pairing.

Kerstin Ekman (b. 1933) provides a literary smörgåsbord to choose from. She is the author of Childhood, and of our recently reissued Women and the City tetralogy. Begin with Witches’ Rings: the central character is a woman so anonymous that her name is not even mentioned on her gravestone. You can read excerpts from Ekman’s other work published in translation by our friends over at Swedish Book Review.

Dorrit Willumsen (b. 1940), author of the novel Bang, came to visit us here at Norvik Press for a chat with her translator, Marina Allemano, about their shared fascination in the (endlessly fascinating!) life of Herman Bang. Bang is welcome to join the party too: he will make a most excellent speaker in the after-dinner slot.

Kirsten Thorup (b. 1942) is unafraid to tackle meaty topics in her work. In The God of Chance, translated by Janet Garton, she unflinchingly explores the problematic relationship between sponsor or donor and recipient. Scenes move from colourful depictions of life in a luxury hotel in Africa, cheek by jowl with desperate poverty, to elite designer flats in Copenhagen, and finally the bustling multicultural community on the streets of London.

Suzanne Brøgger (b. 1944) surely takes the prize for best title with her prose collection, A Fighting Pig’s Too Tough to Eat. Brøgger’s writings transgress genre and have often prompted comparison with her fellow countrywoman, Karen Blixen. This collection traces her development from social rebel to iconoclast and visionary.

Vigdis Hjorth (b. 1959) is an eminent guest. A House in Norway tells the story of Alma, a divorced textile artist who makes a living from weaving standards for trade unions and marching bands. When a Polish family moves into her apartment, their activities challenge her unconscious assumptions and her self-image as a “good feminist”. Is it possible to reconcile the desire to be tolerant and altruistic with the imperative need for creative and personal space?

Happy Women’s History Month and International Women’s Day!

The centenary of voting rights for women in the United Kingdom is today, 6 February, and will be marked with commemorative events round the country in coming weeks and months. The Representation of the People Act 1918 enabled all men and some women over the age of 30 to vote for the first time and paved the way for universal suffrage 10 years later.

The centenary of voting rights for women in the United Kingdom is today, 6 February, and will be marked with commemorative events round the country in coming weeks and months. The Representation of the People Act 1918 enabled all men and some women over the age of 30 to vote for the first time and paved the way for universal suffrage 10 years later.